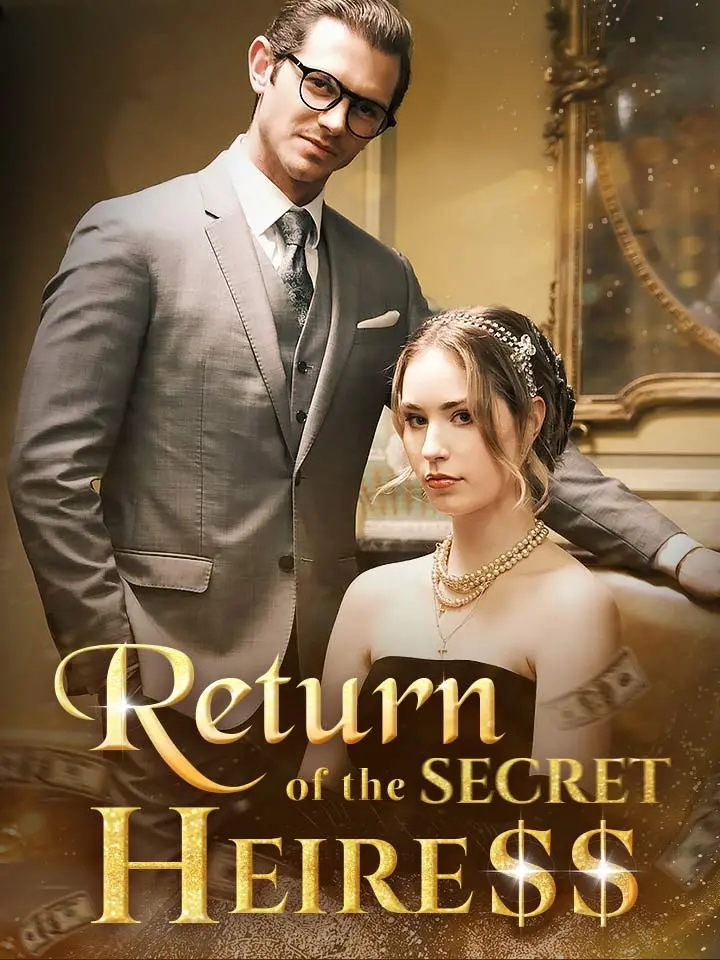

Return of the secret heiressFull Drama

Return of the secret heiress

/0/68276/coverorgin.jpg?v=e850c968fd814f48daf5abddf2735a00&imageMogr2/format/webp)

Rejected No More: I Am Way Out Of Your League, Darling!

For ten years, Daniela showered her ex-husband with unwavering devotion, only to discover she was just his biggest joke. Feeling humiliated yet determined, she finally divorced him. Three months later, Daniela returned in grand style. She was now the hidden CEO of a leading brand, a sought-after designer, and a wealthy mining mogul—her success unveiled at her triumphant comeback. Her ex-husband’s entire family rushed over, desperate to beg for forgiveness and plead for another chance. Yet Daniela, now cherished by the famed Mr. Phillips, regarded them with icy disdain. "I’m out of your league."The old Classical Drama of Greece and Rome died, surfeited with horror and uncleanness. Centuries rolled by, and then, when the Old Drama was no more remembered save by the scholarly few, there was born into the world the New Drama. By a curious circumstance its nurse was the same Christian Church that had thrust its predecessor into the grave.

A man may dig his spade haphazard into the earth and by that act liberate a small stream which shall become a mighty river. Not less casual perhaps, certainly not less momentous in its consequences, was the first attempt, by some enterprising ecclesiastic, to enliven the hardly understood Latin service of the Church. Who the innovator was is unrecorded. The form of his innovation, however, may be guessed from this, that even in the fifth century human tableaux had a place in the Church service on festival occasions. All would be simple: a number of the junior clergy grouped around a table would represent the 'Marriage at Cana'; a more carefully postured group, again, would serve to portray the 'Wise Men presenting gifts to the Infant Saviour'. But the reality was greater than that of a painted picture; novelty was there, and, shall we say, curiosity, to see how well-known young clerics, members of local families, would demean themselves in this new duty. The congregations increased, and earnest or ambitious churchmen were incited to add fresh details to surpass previous tableaux.

But the Church is conservative. It required the lapse of hundreds of years to make plain the possibility of action and its advantages over motionless figures. Just before this next step was taken, or it may have been just after, two of the scholarly few mentioned as having not quite forgotten the Classical Drama, made an effort to revive its methods while bitting and bridling it carefully for holy purposes. Some one worthy brother (who was certainly not Gregory Nazianzene of the fourth century), living probably in the tenth century, wrote a play called Christ's Passion, in close imitation of Greek tragedy, even to the extent of quoting extensively from Euripides. In the same century a good and zealous nun of Saxony, Hroswitha by name, set herself to outrival Terence in his own realm and so supplant him in the studies of those who still read him to their souls' harm. She wrote, accordingly, six plays on the model of Terence's Comedies, supplying, for his profane themes, the histories of suffering martyrs and saintly maidens. It was a noble ambition (not the less noble because she failed); but it was not along the lines of her plays or of Christ's Passion that the New Drama was to develop. It is doubtful whether they were known outside a few convents.

In the tenth century the all-important step from tableau to dialogue and action had been taken. Its initiation is shrouded in obscurity, but may have been as follows. Ever since the sixth century Antiphons, or choral chants in which the two sides of the choir alternately respond to each other, had been firmly established in the Church service. For these, however, the words were fixed as unchangeably as are the words of our old Psalms. Nevertheless, the possibility of extending the application of antiphons began to be felt after, and as a first stage in that direction there was adopted a curious practice of echoing back expressive 'ah's' and 'oh's' in musical reply to certain vital passages not fitted with antiphons. Under skilful training this may have sounded quite effective, but it is natural to suppose that, the antiphonal extension having been made, the next stage was not long delayed. Suitable lines or texts (tropes) would soon be invented to fill the spaces, and immediately there sprang into being a means for providing dramatic dialogue. If once answers were admitted, composed to fit into certain portions of the service, there could be little objection to the composition of other questions to follow upon the previous answers. Religious conservatism kept invention within the strictest limits, so that to the end these liturgical responses were little more than slight modifications of the words of the Vulgate. But the dramatic element was there, with what potentiality we shall see.

So much for dramatic dialogue. Dramatic action would appear to have grown up with it, the one giving intensity to the other. The development of both, side by side, is interesting to trace from records preserved for us in old manuscripts. Considering the occasion first-for these 'attractions' were reserved for special festivals-we know that Easter was a favourite opportunity for elaborating the service. The events associated with Easter are in themselves intensely dramatic. They are also of supreme importance in the teaching of the Church: of all points in the creed none has a higher place than the belief in the Resurrection. Therefore the 'Burial' and the 'Rising again' called for particular elaboration. One of the earliest methods of driving these truths home to the hearts of the unlearned and unimaginative was to bury the crucifix for the requisite three days (a rite still observed in many churches by the removal of the cross from the altar), and then restore it to its exalted position; the simple act being done with much solemn prostration and creeping on hands and knees of those whose duty it was to bear the cross to its sepulchre. This sepulchre, it may be explained, was usually a wooden structure, painted with guardian soldiers, large enough to contain a tall crucifix or a man hidden, and occupying a prominent position in the church throughout the festival. Not infrequently it was made of more solid material, like the carved stone 'sepulchre' in Lincoln Cathedral.

A trope was next composed for antiphonal singing on Easter Monday, as follows:

Quem quaeritis?

Jhesum Nazarenum.

Non est hic; surrexit sicut praedixerat: ite, nuntiate quia surrexit a mortuis.

Alleluia! resurrexit Dominus.

Now let us observe how action and dialogue combine. One of the clergy is selected to hide, as an angel, within the sepulchre. Towards it advance three others, to represent three women, peeping here, glancing there, as if they seek something. Presently a mysterious voice, proceeding out of the tomb, sings the opening question, 'Whom do you seek?' Sadly the three sing in reply, 'Jesus of Nazareth'. To this the first voice chants back, 'He is not here; he has risen as he foretold: go, declare to others that he has risen from the dead.' The three now burst forth in joyful acclamation with, 'Alleluia! the Lord has risen.' Then from the sepulchre issues a voice, 'Come and see the place,' the 'angel' standing up as he sings that all may see him, and opening the doors of the sepulchre to show clearly that the Lord is indeed risen. The empty shroud is held up before the people, while all four sing together, 'The Lord has risen from the tomb.' In procession they move to the altar and lay the shroud there; the choir breaks into the Te Deum, and the bells in the tower clash in triumph. It is the finale of the drama of Christ.

To illustrate at once the dramatic nature and the limitations of the dialogue as it was afterwards developed we give below a translation of part of one of these ceremonies, from a manuscript of the thirteenth century. The whole is an elaborated Quem quaeritis, and the part selected is that where Mary Magdalene approaches the Sepulchre for the second time, lamenting the theft of her Lord's body. Two Angels sitting within the tomb address her in song:

Angels. Woman, why weepest thou?

Mary. Because they have taken away my Lord,

And I know not where they have laid him.

Angels. Weep not, Mary; the Lord has risen.

Alleluia!

Mary. My heart is burning with desire

To see my Lord;

I seek but still I cannot find

Where they have laid him.

Alleluia!

[Meanwhile a certain one disguised as a gardener draws near and stands at the head of the sepulchre.]

/0/4784/coverorgin.jpg?v=b1bae03f3d812030ed7597631da108f2&imageMogr2/format/webp)

The Growth of English Drama

This book (hardcover) is part of the TREDITION CLASSICS. It contains classical literature works from over two thousand years. Most of these titles have been out of print and off the bookstore shelves for decades. The book series is intended to preserve the cultural legacy and to promote the timeless/0/70045/coverorgin.jpg?v=317371d5f8913d87feb1985c9c8e0e11&imageMogr2/format/webp)

The Return of Lyra

Lyra, a young omega in a powerful werewolf pack, has spent years under the tyrannical rule of the cruel Alpha, Raegar. His punishments are harsh, and his abuse leaves her physically and emotionally scarred. Yet, there is a secret within Lyra - a powerful, dormant ability she is unaware of. With the/0/20581/coverorgin.jpg?v=c387cde452c24ed0373116c0df627caf&imageMogr2/format/webp)

Return Of The Nerd

Adrianna Rodriguez is humiliated by her boyfriend when she finds him cheating on her at school. Distraught she leaves home for a year and focuses on herself. When she returns she is dead set on getting revenge what she didn't expect was to form a relationship with her ex's enemy. Together they tea/0/36284/coverorgin.jpg?v=3a8dbc4abbf976361442c1669e2dba40&imageMogr2/format/webp)

Drama Queen

Nicole Vargas. Spoiled, rich, smart, and melodramatic. She graduated Fashion Design in Brazil and was the daughter of a well known artist and the CEO of 'The Vargas' hotel and casino chains. She could get anything she wants at just the snap of her fingers. Even her career. But she didn't. And she/0/26083/coverorgin.jpg?v=0709970bfecd1f5fe412002907769292&imageMogr2/format/webp)

Dawn Of No Return—Pride Of The Secret

Right after his first encounter with The Secret, Grey enjoys the comfort of his home when he is called back to service to serve The Secret, a force he can't say no to. This time, she gives him various tales, like avenging the dead, and his favourite, looking after Helen./0/1590/coverorgin.jpg?v=db9bfdf5a5cb4e3e00e5825716b6f1a2&imageMogr2/format/webp)

The Return of Tarzan

In this second addition to Edgar Rice Burroughs' epic adventures of Tarzan, listeners will find the jungle man leaving America to visit old friends in Europe. Through spirals of action, disaster, and shipwreck, we find Tarzan and a group of travelers, including his first love Jane and his new archen/0/57031/coverorgin.jpg?v=45534e54ad36109b6f207435dbe4052f&imageMogr2/format/webp)

Return Of The Rejected

"I was always sincere with you, Why did you betray me this way? How can you accuse me of such despicable things?" Karlie questioned, her eyes fighting back hot tears but the man she was talking to wasn't paying attention. "Let's not see each other again." °°°°°° Karlie met Cillian in the most u/0/34591/coverorgin.jpg?v=977c05e0ca9acf231d51b0abafcdfc17&imageMogr2/format/webp)

The Return of Lycans

"Why, little princess? Does my proximity make you nervous?" Asked Zarek, in his velvet voice. Glaring at him, "Your presence suffocates me." Said Crystal, bitterly. "Really," Smirking, Zarek chuckled and said, "You didn't seem to complain last night." Zarek's remark elevated the frustration level/0/44023/coverorgin.jpg?v=84df0ebb4b50fc88eb28be29539a7c6b&imageMogr2/format/webp)

The Return of Luna

She was born as the legitimate daughter of Beta Henry's wife, enduring hardship for eight years before finally becoming the Luna of the Lycan King. However, fate was cruel as her husband fell in love with her elder sister and stripped her of her Luna position, forcing her son to die! In the cold and/0/70182/coverorgin.jpg?v=8f267ab7952cd1d0b756c163f3f7689c&imageMogr2/format/webp)

The Return Of The Alpha

Nicholas born into a long line of the Senior Elder blood which is almost extinct, except for him and his mother Victoria (Camrial) who died when he was only ten after calling him a Senior Elder, without explaining any further. Nicholas grew up unaware of the extent of his powers. He lived hidden/0/38436/coverorgin.jpg?v=2a003a131eb59a1b6b2ddd7f949a990e&imageMogr2/format/webp)

Teen drama

Kayla is a smart, focused, top-mark student in her last two senior years of high school in a private facility for rich kids in Florida. All she wants is to get accepted to Harvard and graduate with top marks to follow the career she has set for herself. Her entire life is about becoming an independe/0/199/coverorgin.jpg?v=20171219150553&imageMogr2/format/webp)

The Return of the Native

The novel takes place entirely in the environs of Egdon Heath, and, with the exception of the epilogue, Aftercourses, covers exactly a year and a day. The narrative begins on the evening of Guy Fawkes Night as Diggory Venn is slowly crossing the heath with his van, which is being drawn by ponies. In/0/50553/coverorgin.jpg?v=4764b702c83b2d847995166c90eafaee&imageMogr2/format/webp)

The Return of the Legends

The Swordsman's Era was a time when swordsmen fought for their home. Their opponents were unlike anything they'd encountered before. They are unworldly beings who have come from the darkest dimensions to conquer the world. Shikari, a swordsman who stood differently from the rest, was tasked with a m/0/80393/coverorgin.jpg?v=c161371dde5d53b301c436700b372ff2&imageMogr2/format/webp)

The Return of the Novice

They called her "The Novice" - a girl destined only to tend ancient halls and copy dusty scrolls. But destiny had other plans. When the sacred flames flicker and ancient darkness rises, Emily must journey beyond the world she knows - through ruined temples, forbidden valleys, and memories that thre/0/1612/coverorgin.jpg?v=20171123180032&imageMogr2/format/webp)

The Caillaux Drama

Late on Monday afternoon, March 16, 1914, a rumour fired imaginations, like a train of gunpowder, all over Paris. In newspaper offices, in cafés, in clubs, people asked one another whether they had heard the news and whether the news were true. It seemed incredible. The wife of the Minister o/0/5113/coverorgin.jpg?v=d3f35bfa1eb9e9bb35c37ef8950f490d&imageMogr2/format/webp)

/0/22921/coverorgin.jpg?v=0022ccac44c63ee0a3ed6456745386ae&imageMogr2/format/webp)

The Return of the Souls

It is a story of the two rival kings in ancient time who reincarnate as man and woman, fall in love with each other, and get married as a punishment from God for their mortal sins of exploiting the lives of their warriors. From time to time, their instincts as rival kings come out and they fall into/0/20387/coverorgin.jpg?v=e7964c940b9a30f19f7aef8a42f2e32c&imageMogr2/format/webp)

Marriage drama

💓 Marriage 👰 drama 💓 I just wanna keep my marriage Prologue Meet Ryan Gold.. The CEO of "Ryan enterprises company." one of the youngest billionaire in the country. He is just 25years.handsome jerk..you can say that again he is very handsome and grumpy.. he is sweet but only to his mother Every/0/32939/coverorgin.jpg?v=20220922161728&imageMogr2/format/webp)

/0/54696/coverorgin.jpg?v=83f45ec964bc040119cdc41715809913&imageMogr2/format/webp)